Can A Nonprofit Board Member Be Paid For Services?

(Illustration by iStock/Flash vector)

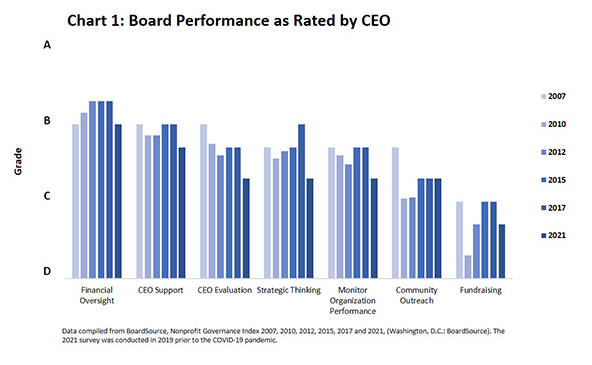

Nonprofit governance is tough and getting tougher. As a result, nonprofit boards are increasingly challenged to consistently evangelize high-quality governance. Well-intentioned efforts to improve governance by reducing board size, restructuring standing committees, or identifying best practices take non resulted in demonstrably improve governance quality across the nonprofit sector. BoardSource's 2021 Leading with Intent: BoardSource Index of Nonprofit Board Practices survey shows that board functioning, every bit rated by a diverse mix of nonprofit CEOs, receives middling grades for central responsibilities. Looking at results over time (Chart one), these responsibilities appear stuck in a rut that is not every bit skilful as the nonprofit sector needs!

In research recently conducted for the Center for Social Sector Leadership at UC Berkeley'southward Haas School of Business nosotros explored a new idea: Would designating one board member to serve as a Master Governance Officer (CGO) improve nonprofit governance? Interviews with 30 experienced nonprofit directors representing over 100 nonprofit boards supported the hypothesis that a CGO could catalyze improved board operation.

While the CGO title itself was questioned by some, it is intended to convey both an aspiration and a position of importance. Drawing on the feedback of our interviewees, this article summarizes the common sources of inconsistent governance quality and outlines the expected benefits of appointing 1 director as a CGO.

Eight Sources of Inconsistent Governance

Why does nonprofit governance fall brusque of the ambitious goals of the sector? Our review of existing board leadership surveys—nigh helpfully BoardSource'due south Leading with Intent: BoardSource Index of Nonprofit Board Practices and Stanford University'due south 2015 Survey on Board of Directors of Nonprofit Organizations—and the experience of the directors we spoke with collectively highlighted eight sources of inconsistent governance.

1. Nonprofit directors often lack a shared understanding of what adept governance means. Few of the directors we spoke with defined "governance" the same style. Whether due to the lack of a universally accepted definition of governance, or the lack of standardized training when joining a nonprofit board, too many directors bring only a fractional sense of the commitments they have accepted upon taking a board seat. If held at all, nonprofit board orientation programs are often created and driven by staff members to introduce new directors to the arrangement, simply rarely include a director-driven discussion of the board'south office, governance responsibilities, and how the board organizes itself to fulfill those responsibilities. Poor initial training and a lack of continuing manager education perpetuates an underemphasis on governance and handicaps the board'southward ability to be effective partners in driving organizational performance. One of our interviewees concluded: "Nosotros fail from the very beginning."

2. Nonprofit boards practice not always take the correct voices in the boardroom. Most boards know they perform better when they have a strong, diverse prepare of directors sitting effectually the board table working effectively as a squad. Driven by the need for fundraising help, nonetheless, many boards prioritize financial capacity and personal networks at the expense of community representation, professional skills in areas such as technology or social media, or other governance-relevant attributes. Many of the directors we spoke with noted that organizations were actually "wrestling with Variety, Equity, and Inclusion" (DEI), and that "DEI is really easy to screw upwardly." Finally, the fourth dimension commitment necessary and fundraising obligations associated with board service were both commonly cited as barriers to recruiting both younger and more diverse candidates.

iii. Pressure to help organizations meet annual fundraising targets shifts attention away from governance. Stanford'due south 2015 Survey on Board of Directors of Nonprofit Organizations reported that most one-half of nonprofit boards require board members to fundraise, and on those boards "90 pct of respondents believe that fundraising is every bit or more important than their other obligations equally directors." Indeed, fundraising obligations often pull board attention from other governance responsibilities and encourage boards to grow, but at the toll of reduced ability for the board to piece of work generatively and strategically equally an effective team.

iv. Boards fail to regularly assess governance performance and develop improvement plans. BoardSource's 2021 Leading with Intent survey notes that just 47 percentage of boards take completed a self-assessment in the terminal ii years, and almost 1-third of responding organizations have never completed a self-cess. BoardSource surveys over the years prove that boards that regularly self-appraise perform better against fundamental governance responsibilities than boards that do not.

5. Poor governance processes push button boards to underinvest in critical problems and governance activities. Weak governance processes contribute significantly to inconsistent governance. Inefficient meetings, poor facilitation, and unwieldy agendas pull fourth dimension from critical topics. Outdated committee structures, underperforming committee leadership, or lack of annually updated plans fails to ensure that committees are focused and accountable. A bias towards consensus too often leads boards to rubber postage decisions, and inadequate preparatory materials coupled with tight timelines leave boards struggling to contend complex issues, explore strategic choices, or act with confidence. Finally, a lack of authentic key performance indicators leaves boards wondering nearly the real performance of the system and whether they know enough to provide well-informed direction.

6. A low-accountability lath culture leads to inconsistent effort by individual directors. Experts agree and our interviewees confirmed that a strong board culture "has a significant influence on the way [a] lath carries out its work." Ofttimes, however, voluntary lath work takes a back seat to directors' day jobs, leading to poor preparation for board participation and controlling. A weak board civilisation often manifests itself in "nonprofit squeamish" advice and fails to agree underperforming directors accountable for quality engagement. Unlike public corporate boards, nonprofit self-assessment processes rarely ask directors to evaluate the functioning of their fellow board members, which can contribute to a low-accountability culture. The Stanford survey cites that "almost half of respondents do not believe that their fellow board members are very engaged in their piece of work, based on the time they dedicate to their organization and their reliability in fulfilling their obligations."

7. Confusion between the board'south part and that of direction. Equally passionate volunteers, nonprofit directors can overstep boundaries and get too involved in the day-to-day activities of the organisation, frustrating nonprofit managers and diverting fourth dimension from more appropriate governance topics. Leading with Intent notes that "the board'south agreement of roles and responsibilities is fundamental to the lath's performance," and supports the statement with assessment data that shows "boards that have a stiff agreement of roles also tend to accept stronger performance across all other [board] performance areas."

8. Governance has gotten tougher. The world is changing in ways that expose weak governance practices. The overwhelming majority of our interviewees agreed that governance is getting tougher, which has multiplied the risks facing the reputation and finances of nonprofits. Commonly cited challenges that boards now grapple with include:

- Financial complication: The fiscal impact of the pandemic and increasingly circuitous business models take resulted in financial oversight that is "wider and deeper than it used to be."

- Engineering science: Digital tools enable nonprofits to digitize records, access new audiences, reimagine programs, and assess impact with amend data than ever before. Still, these opportunities oft crave pregnant investments and can betrayal nonprofits to data theft and privacy issues.

- Sociocultural shifts: Societal reckoning with systemic racism has prompted many nonprofits to rethink assumptions and renew commitments to Diversity, Disinterestedness, and Inclusion (DEI) in their programming, staffing, and board composition.

- Increased public scrutiny: Rating agencies have established new standards for transparency that make the impact of board decisions available for all to come across. Meanwhile, social media has created a new level of exposure and chance for a nonprofit's public reputation while elevating expectations for rapid responses to unfavorable news items. Partnerships with both for-turn a profit companies and other nonprofits further complicate nonprofit governance as public controversies surrounding partners can create new reputation management dilemmas.

- Evolving legal duties: Contempo legal decisions are raising expectations for how boards fulfill their duty of care and loyalty. Changes in corporate compliance law suggest that nonprofit boards, like their for-profit counterparts, are increasingly liable for their system's activity, fifty-fifty in the absence of information.

All these issues require boards to be on the lookout for the next big issue or risk, which is where a CGO could aid. We asked our panel of experienced directors whether appointing one board member as a CGO would effect in a higher level of board attention to these and other important governance issues and thereby help boards lift their governance game. The overwhelming response was Aye, with 97 per centum assertive a CGO would be helpful in all or in many situations.

Defining the CGO Function

The CGO role that emerged from our conversations was one of an internal governance quality advocate who helps the lath comprehensively engage with its governance obligations. In this capacity, the CGO has two central areas of oversight:

1. Ensure compliance with legal and social expectations. The CGO should inquire questions to ensure the board and organization comply with current and emerging legal and ethical standards to preserve the organisation's license to operate in the community. On behalf of the lath, the CGO should manage and update the list of compliance expectations; collaborating with staff and the board to ensure all standards are met and accurately reported. The CGO should, by definition, accept strong awareness of the organization's bylaws and policies, which are the foundational documents informing board governance requirements.

2. Champion the adoption of proven governance practices that enable the board to help the organisation fulfill its mission finer and efficiently. To attain infrequent governance, the CGO'southward oversight must be complemented by a commitment to adopting board practices known to support system performance and mission fulfillment. These practices and mindsets are an e'er-evolving listing, with BoardSource CEO Anne Wallestad's 2021 SSIR article "The Four Principles of Purpose-Driven Board Leadership" equally the latest contribution in this field. A disquisitional aspect of the CGO'south responsibleness is to ask: "What aren't nosotros doing that would help our nonprofit perform amend?"

While the CGO cannot singlehandedly deliver high quality governance, as an advisor to the whole board and a thought partner to the decorated lath chair they tin pose the right questions to stimulate thoughtful board discussion. Interviewees agreed that comparing board practices confronting an accepted list of good governance questions would exist a strong starting point for a CGO. For example: Are our nonprofit's articles, bylaws, and board-approved policies up-to-appointment and in compliance with legal obligations and societal expectations? Does the lath annually review CEO performance and update their goals? Does the Board regularly review a prepare of key operation indicators to runway organization bear upon, financial functioning, and overall health? Using resources available in the sector, we assembled a working list of questions roofing a wide range of topics that a CGO could utilize to prompt a lath to recognize and address gaps. The full listing is available here.

In improver to asking questions that prompt lath reflection and action, the CGO should play a hands-on part in iv activities:

- Leading a bi-annual review of governance effectiveness and monitoring initiatives to improve board performance.

- Driving new director governance grooming and shaping supplemental training and didactics over time.

- Monitoring external governance-related developments pertaining to the constabulary, regulations, and social expectations on behalf of the board.

- Engaging with the CEO on how staff tin can best support high quality governance past, for example, ensuring appropriate board materials are prepared and/or framing board discussions to encourage appointment with genuine issues.

These main responsibilities define a CGO office that will be of value to many boards past addressing the sources of inconsistent governance. The experienced directors we spoke with noted, for example, that a CGO driving regular board self-assessment and strengthening the governance focus of new manager orientation could aid build a stronger shared understanding of what proficient governance means and reduce confusion on the roles of the board and direction. Besides, a CGO working with the board chair and CEO to develop an annual lath calendar and committee mandates would aid ensure that the full range of governance responsibilities, particularly compliance oversight, are regularly addressed each year. In improver, a CGO participating in the nominating process could encourage an equal accent on recruiting for diversity and skill set as for individual fundraising capacity. Our interviewees were especially interested in the value a CGO might add to boards looking to anticipate, rather than react to, irresolute legal or societal expectations by actively monitoring external governance-related articles and forums.

I might question whether the responsibilities outlined higher up are the work of a skilful governance committee. Unfortunately, as many as half of nonprofit boards do not have a commission defended to governance. For those that practice, they are often combined with nominating responsibilities into a single committee, with the reality that the challenges and urgency of filling empty board seats frequently means the nominating part oftentimes trumps the sometimes mundane aspects of governance cess and improvement initiatives. The CGO role seeks to rebalance this natural bias.

Identifying the CGO

Who is best suited to serve equally this expert governance catalyst? This answer will vary past organization. Importantly, naming a CGO does non require a nonprofit to dismantle existing structures or committees. A CGO should be able to work inside existing committee and leadership structures and remain effective despite inevitable board leadership transitions.

Skill set is the critical driver of an individual'southward ability to fulfill the CGO role. First and foremost, mindset is cardinal. An contained, objective, organization-beginning mindset and willingness to inquire difficult, sometimes uncomfortable questions is essential to this role. This may be challenging for existing board leaders already in the center of the governance process. Secondly, legal skills are squeamish to take, but not essential. Communication and persuasion skills are every bit of import as technical noesis. Specific legal expertise tin be acquired pro bono or at a reasonable cost if a legal professional is not already on the board or staff. Finally, training is necessary. A CGO should be trained in board governance, ideally through a formal training or certification program, or via the experience of serving on multiple stiff boards.

The CGO must be on the board. While a few interviewees suggested an external counselor or staff member could fill the role, virtually felt that the CGO needs to be a respected leader on the board able to credibly raise and address issues when they happen. So, who should this person be? There is tremendous variability in the means nonprofits deploy leadership to oversee and support their activities. Whether a board creates a new position or repurposes an existing role, nonprofits have a rich set of options to implement the CGO model:

Board chair: The lath chair has the greatest influence on governance quality in almost nonprofits and could exist a logical candidate for the CGO function. In fact, "Chair as CGO" was the initial hypothesis of our research. Recasting the lath chair as a lath governance expert, particularly in the face of a potent CEO/ED, could help underline the board'south function and reduce take chances for the organization. We recognize, still, that the chair role is already a demanding volunteer job, and chairs are often selected for different strengths, like fundraising skills or a high-profile reputation. Not to mention that in certain situations, the chair can be part of the governance trouble.

Vice chair: The vice chair is often an underutilized role in many nonprofits, and the CGO designation could reinvigorate the position with a well-defined purpose. Re-envisioning the vice chair as CGO could also serve every bit a development opportunity for future chairs.

Chair of a standalone governance committee: Combined nominating and governance committees were commonly described equally allocating their time to "ninety percent nominating and 10 percent governance" issues. A CGO leading a refocused, standalone governance commission would add heft and capacity to support the board'due south most disquisitional role.

Executive commission: The CGO part could as well be formalized as a responsibility of the executive commission or added to the responsibleness of an existing executive commission fellow member or board officer. Our discussions suggested that in loftier performance boards, strong executive committees could exist constructive arbiters of skilful governance.

Independent director: Last and by no means least, an experienced director with the correct skillset might take on the role, particularly on a smaller lath or one with few committees.

It is clear that no ane size fits all and that the tremendous diverseness of nonprofits makes the choice of who to fill the part a far more nuanced and localized one.

Implementing the CGO Role

Our hope is that boards do not allow these variables to get in the way of testing the concept. Permit local factors to shape how the CGO is selected and learn what works best for your organization. To implement the role effectively, nosotros advise the following deportment:

Recruit the skill set up and be prepared to waive other lath expectations (i.east., give-go fundraising requirements, other committee memberships) to get and retain the correct candidate. A CGO's responsibilities will exist fourth dimension consuming and crave a meaningful commitment outside of board meetings.

Brand CGO an officer of the board and/or a member of the executive commission. The CGO must exist seen every bit a existent leadership office inside the lath with a ii- or three-yr term and a maximum of six years in the function.

Accept the CGO report to the lath, non the chair. The CGO should regularly study on governance topics, as part of regular committee chair reports. This approach reinforces the advisory role the CGO plays to the entire lath and helps ensure that important perspectives are not stifled past the board chair.

Sponsor the CGO to receive governance training and certification. As a CGO is a new concept, at that place are not notwithstanding training programs that focus specifically on this role, only there are a multifariousness of governance-oriented training programs and resources available in the nonprofit sector.

Support the CGO's membership in good governance forums such as those provided by BoardSource, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), or the Women Corporate Directors Foundation (WCD).

Accommodate for access to outside counsel so the CGO can hash out issues and only bring forward those which deserve board consideration. Peculiarly for a CGO without legal training, access to pro bono counsel or a minor upkeep for external legal advice (bold no internal counsel) volition give the CGO confidence and avoid wasting the full board's time on problems where the law is articulate.

Consider adopting the role on a temporary ground. Boards who wonder whether the CGO is valuable can prefer the role for a two-year trial. Preceding the adoption with a cocky-assessment and following up two or so years later with another cocky-assessment will enable the lath to assess whether the role made a meaningful difference.

Too many nonprofit boards are stuck in a rut of substandard governance and need a new way to break out. The majority of our interviewees felt that designating a CGO to help nonprofit boards lift their governance game is a new idea whose fourth dimension has come. For boards struggling with governance, it is a low-cost, applied solution with significant upside. The best manner to answer the question of whether appointing a CGO on your nonprofit board is a worthwhile exercise is to have an informed director answer our suggested CGO questions and see whether gaps in electric current practices merit an investment in catalyzing better governance. For many nonprofits, we believe the answer will be yeah.

Organizations interested in implementing the CGO office are invited to contact the authors at [email protected] and [electronic mail protected] for farther information.

Read more stories by Paul Jansen & Helen Hatch.

Source: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/does_your_nonprofit_board_need_a_cgo

Posted by: packardunrarken.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Can A Nonprofit Board Member Be Paid For Services?"

Post a Comment